By Ross Bishop

In the 12th century, Persian culture had reached a pinnacle of understanding that is as yet unmatched in human history. Although birthed in a Muslim environment, Sufism is not attached to any religion. It can best be thought of as a metaphysical philosophy rather than as a religion.

The method developed by the Persians has a logical foundation, but it transcends that into a non-linear realm that can only be understood by metaphor. Its structure reaches deeply into higher levels of consciousness. These metaphors upon which Sufism is based, build a bridge from the logical to the metaphysical, confusing people who have been brought up in the Western intellectual tradition. And these metaphors also transcend language, making them difficult to explain.

Western logic builds linearly and rationally: A to B to C, etc. And the mathematical symmetry of this logic works beautifully to explain the structure of the atom, the temperature of stars or the growth of bacteria. But logic is not well equipped to deal with subjects outside those realms, such as metaphysical subjects like love, music, poetry or for that matter, God.

Sufic teachings might have gained wider acceptance were it not for the intrusion of Genghis Khan’s barbarians in 1220. Khan’s henchmen ruthlessly slew anyone in Persian society who had even a smidgeon of education. Sadly, Sufism has also been shunned by Western intellectuals because it came from the Muslim East and it threatened the rational foundations of Western culture during the late Middle Ages through the Medieval period, when The (anti-Muslim) Crusades to recapture the Holy Land were in full swing. Sufic teachings had also found their way into Spanish culture, and challenged the rigid orthodoxy of the Catholic Church. The fact that The Inquisition was concentrated in Spain was not an accident.

Fortunately the writings of the Sufi teachers such as Rumi and his teacher Farid ud-Din Attar, and Adil Alimi, Saadi, Ghazali and Ibn El-Arabi have been preserved. They even reached and influenced Western thinkers like Chaucer, Thomas Aquinas, Francis Bacon and St. Francis of Asssi, who incorporated this approach into their own works.

The lessons I speak of are usually conveyed through allegories, using the Mullah Nasrudin as a central figure. As you read them, aside from their momentary humor, look for the deeper meaning in each one. Here are a few:

The Mullah had returned to his village from the imperial capital, and the villagers gathered around to hear what he had to say of his adventures.

At this time,’ said Nasrudin, ‘I only want to say that the King spoke to me.’

There was a gasp of excitement. A citizen of their village had actually been spoken to by the King! The titbit was more than enough for the yokels. They dispersed to pass on the wonderful news.

But the least sophisticated of all hung back, and asked the Mulla exactly what the King had said.

‘What he said — quite distinctly, mind you, for anyone to hear — was “Get out of my way!”’

The simpleton was more than satisfied. His heart expanded with joy. Had he not, after all, heard words actually used by the King; and seen the man to whom they had been addressed?

The story’s obvious meaning has to do with name droppers, but in addition to being entertaining, there are also several deeper levels of meaning to be found. And this is where their real power lies. A few more examples:

Nasrudin walked into a shop one day, and the owner came forward to serve him. Nasrudin said, "First things first. Did you see me walk into your shop?" "Of course,” said the shop owner. "Have you ever seen me before?” “Never," replied the owner. “Then how do you know it was me?” asked Nasrudin.

And another:

Nasrudin walked into a teahouse and declaimed, "The moon is more useful than the sun." “Why?" he was asked. "Because at night we need the light more.”

This next one is one of my personal favorites:

Nasrudin the smuggler was leading a donkey that had bundles of straw on its back. An experienced border inspector spotted Nasrudin coming to his border. "Halt," the inspector said. "What is your business here?" "I am an honest smuggler!" replied Nasrudin. "Oh, really?" said the inspector. "Well, let me search those straw bundles. If I find something in them, you are required to pay a border fee!" "Do as you wish," Nasrudin replied, "but you will not find anything in those bundles.” The inspector intensively searched and took apart the bundles, but could not find a single thing in them. He turned to Nasrudin and said, "I suppose you have managed to get one by me today. You may pass the border." Nasrudin crossed the border with his donkey while the annoyed inspector looked on. And then the very next day, Nasrudin once again came to the border with a straw-carrying donkey. The inspector saw Nasrudin coming and thought, "I'll get him for sure this time.” He checked the bundles of straw again, and then searched through the Nasrudin's clothing, and even went through the donkey's harness. But once again he came up empty handed and had to let Nasrudin pass. This same pattern continued every day for several years, and every day Nasrudin wore more and more extravagant clothing and jewelry that indicated he was getting wealthier. Eventually, the inspector retired from his longtime job, but even in retirement he still wondered about the man with the straw-carrying donkey. "I should have checked that donkey's mouth more thoroughly," he thought to himself. "Or maybe he hid something in the donkey's rear end.” Then one day he spotted Nasrudin's face in a crowd. "Hey," the inspector said, "I know you! You are that man who came to my border everyday for all those years with a donkey carrying straw. Please, sir, I must talk to you.” Nasrudin came towards him and the inspector continued talking. "My friend, I always wondered what you were smuggling past my border everyday. Just between you and me, you must tell me. I must know. What in the world were you smuggling for all those years? I must know!" Nasrudin simply replied, “Donkeys."

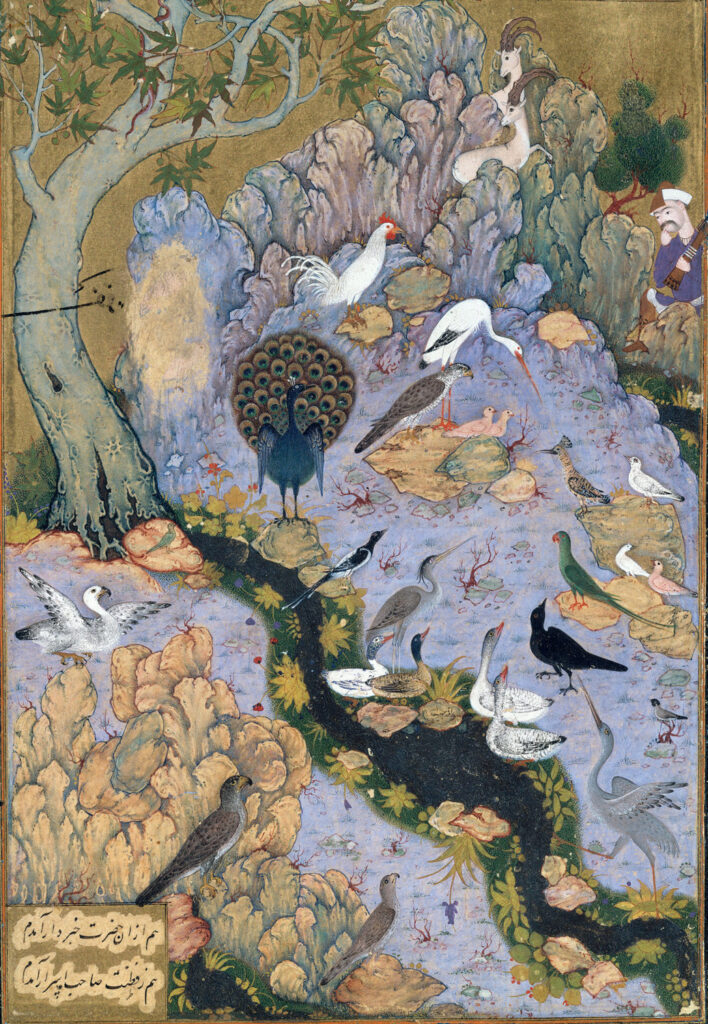

In 1177 Farid ud-Din Attar composed “Mantiq ut-Tayr,” or “The Parliament of the Birds,” (in Arabic: منطق الطیر). This very long allegory (4500 lines) is one of the greatest and most influential Sufi poems of all time. Attar was embedded in the long Persian tradition of mystical poetry that served both to express the wonder and joy of the spiritual path but also to offer guidance to the seeker on how to do the hard work of opening one’s heart to the divine. Attar’s allegory tells the story of a group of birds setting out to find God and enlightenment.

In the poem, the birds of the world are called together by the hoopoe, (the hawk), to decide who is to be their king. After all, the jungle animals have the lion as their king, man has kings, the whales rule the oceans, etc. So why not birds? The hoopoe proposes that they should start on a quest to find their mysterious king called Simurgh, a mythical bird roughly equivalent to the western phoenix who lives in the Mountains of Kaf.

The Simurgh is a fabulous, benevolent, mythical flying creature that was thought to purify the land/water, and hence bestow fertility. The Simurgh represented the union between the Earth and the sky, serving as mediator and messenger between the two. Legends consider the bird so old that it had seen the destruction of the world three times over. The Simurgh learned so much by living so long that it was thought to possess the knowledge of the ages.

The hoopoe leads the birds, each of whom has both a special significance and a corresponding human didactic fault, which prevents humans and birds from attaining enlightenment. Despite their ardent desire to draw closer to the unparalleled beauty, the birds are hesitant, afraid to engage. Each bird, after first being excited by the prospect, begins to make excuses as to why he should not himself take part in the journey. And one by one, they drop out, each offering an excuse about being unable to endure the journey.

The hoopoe works hard at convincing them to engage in this quest. After hearing their pleas, he replies with a tale illustrating the uselessness of preferring that which one has or might have to what one should have. He tells the other birds that the quest they are about to undertake is a long journey and will require that they travel through seven valleys, each of which will require them to confront some inner weakness, some moral failing. These symbolize the different stages one must go through in order to defeat the ego.

The Seven Valleys

The first valley is The Valley of The Quest, (Talab) or yearning where all kinds of perils threaten, and where the pilgrim must renounce all desires.

The second valley is The Valley of Love, (Ishq), representing the limitless state in which the seeker is completely consumed by a thirst for the Beloved. I want to present to you the dialogue between the nightingale symbolizing the lover and the hoopoe so that you might get a sense for the larger allegory:

The Nightingale’s excuse

The nightingale made his excuses first.

His pleading notes described the lover’s thirst,

And through the crowd hushed silence spread as he

Descanted on love’s scope and mystery.

‘The secrets of all love are known to me,’

He crooned. ‘Throughout the darkest night my song

Resounds, and to my retinue belong

The sweet notes of the melancholy lute,

The plaintive wailing of the lovesick flute;

When love speaks in the soul my voice replies

In accent plangent as the ocean’s sighs.

When winter comes I see my love has gone –

I’m silent then, and sing no lover’s song!

But when the springs return and she is there

Diffusing musky perfumes everywhere

I sing again, and tell the secrets of

My aching heart, dissolving them in love.

The men who hears this song spurns reason’s rule;

Grey wisdom is content to be love’s fool.

My love is for the rose; I bow to her;

From her dear presence I could never stir.

If she should disappear the nightingale

Would lose his reason and his song would fail,

And through my grief is one that no bird knows,

One being understands my heart – the rose.

I am so drowned in love that I can find

No thought of my existence in my mind.

Her worship is sufficient life for me;

The quest for her is my reality

(And nightingales are not robust or strong;

The path to find the Sîmorgh is too long).

My love is here; the journey you propose

Cannot beguile me from my life – the rose.

It is for me she flowers; what greater bliss

Could life provide me – anywhere – than this?

Her buds are mine; she blossoms in my sight –

How could I leave her for a single night?’

The Hoopoe answers him:

‘Dear nightingale,

This superficial love which makes you quail

Is only for the outward show of things.

Renounce delusion and prepare your wings

For our great quest; sharp thorns defend the rose

And beauty such as hers too quickly goes.

True love will see such empty transience

For what it is – a fleeting turbulence

That feels you sleepless nights with grief and blame –

Forget the rose’s blush and blush for shame!

Each spring she laughs, not for you, as you say,

But at you – and has faded in a day.

The Valley of Love is followed by the Valley of Intuitive Knowledge, (Ma’rifat or Gnosis), in which the heart receives directly the illumination of Truth and an experience of God.

In The Valley of Detachment, (Istighnah), the traveler becomes liberated from desires and dependence.

The fifth valley is The Valley of Unification (Tawheed, or the Unity of God). In this place the seeker comes to understand that things and ideas which seemed to be different, are actually only one.

In the sixth, The Valley Of Astonishment (Hayrat), the traveler finds bewilderment and also love. He no longer understand knowledge as before. Something, called love, replaces it.

The seventh and final valley is The Valley of Death, (Fuqur and Fana i.e. Selflessness and Oblivion in God) is where the seeker comes to understand the mystery, the paradox, of how an individual “drop can be merged with an ocean, and still remain meaningful. He has found his place.”

These represent the stations that the individual must pass through to realize the true nature of God. Within the larger context of the story of the journey of the birds, Attar masterfully tells the reader many didactic short, sweet stories in captivating poetic style.

In the end, only thirty of the birds will reach their goal. When the group finally reaches the dwelling place of the Simurgh, they find only a lake in which they see their own reflection – not the mythical Simurgh which they have been seeking. They come to understand that the Truth they were seeking was within each of them all the time, (so close and yet so far away). As the birds come to realize the truth, they now reach the station of Baqa (Subsistence) which sits atop the Mountain Qaf.

copyright ©2021 Blue Lotus Press