by Ross Bishop

For thousands of years, there has been a conflict in society between those who sought power and those who live lives of compassion and caring. The evolution of society toward greater compassion is clear. It has sometimes been a challenging journey, but the overall trend is evident. The process has involved gaining rights, starting from powerless slavery to today. In the beginning, people had no rights, little dignity and were at the mercy of those who ruled them. Changes over time were either granted out of compassion or forced from those in power. Today, although we still have a ways to go, we enjoy greater equality, more freedoms and stronger legal protections than ever before.

This article provides a brief overview of the complex and interconnected path toward greater compassion. I will use milestones from Western historical events to illustrate this transition. We could do the same study by using art or music, but my training does not equip me in those directions. My focus will be on Western culture because it is simply easier to follow its historical development.

Many advanced and enlightened tribal societies have existed over the period, but because human civilization has largely remained isolated throughout its history, until the recent invention of the printing press. Although we can't precisely measure individual compassion levels, our various political milestones serve as good indicators of overall social conditions, at least here in the West.

We must remember that throughout history, spiritual teachers such as the Buddha, Christ, Lao Tzu, Confucius, Babaji, the shaman of Mongolia and the Maya and the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita have inspired people to develop greater care and compassion for one another.

The Early Foundations

The ideas of human dignity and limits on violence existed in some ancient Western cultures. One of the earliest examples we have is the Code of Hammurabi. Hammurabi was the sixth King of Babylon ( 1780 BC). His code outlines rules and punishments for violations, including those concerning the rights of women, men, children, and slaves.

(The Code of Hammurabi)

The concept of human rights in ancient Egypt was deeply embedded in the principles of Ma'at, the female goddess representing truth, order, balance, and justice. Pharaoh Bocchoris (725–720 BC) advocated for individual rights, abolished imprisonment for debt and reformed laws related to property transfers for citizens. All citizens (except slaves) were regarded as equal and had the right to own property and receive fair treatment in court. Laws were created to protect citizens from harm and to ensure fairness in legal proceedings. Citizens were allowed to express their thoughts without fear of retaliation.

(Ma’at)

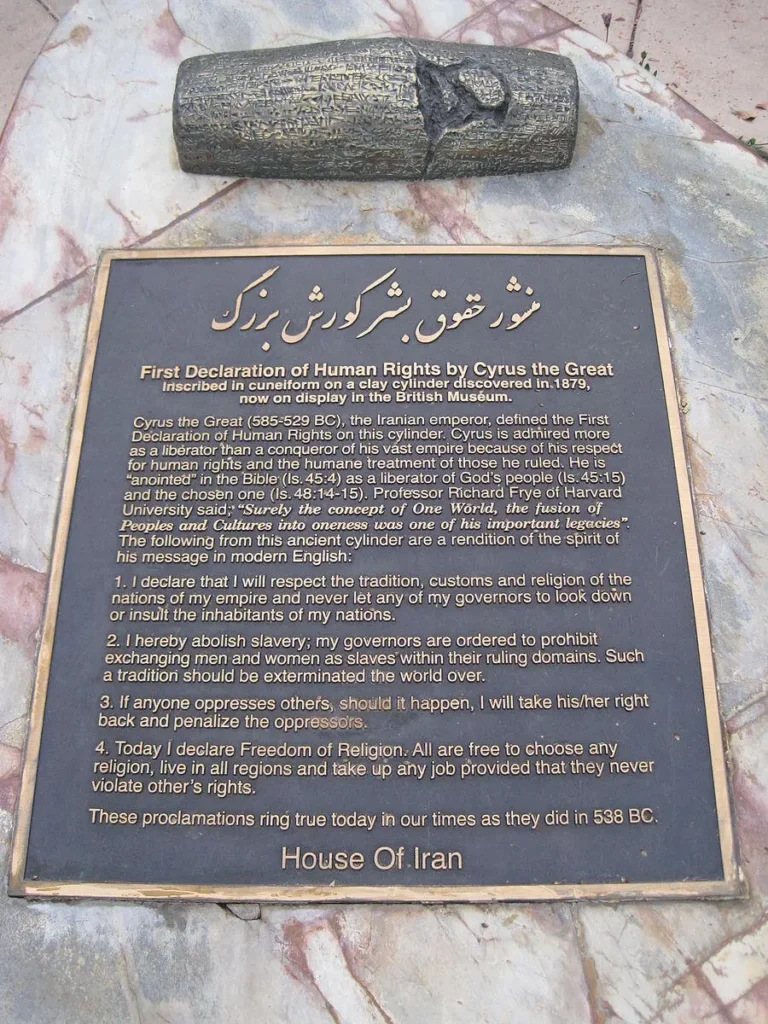

When King Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylonia in 539 BC, he issued a decree supporting religious freedom and tolerance. He also granted freedom to formerly enslaved and exiled peoples in these lands and allowed captives of the former Babylonian king to return to their homelands. Among those exiled were Jews, whom Cyrus permitted to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their temple.

(Cyrus’ Decree)

The Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, who ruled from 268 to 232 BC, established the largest empire in South Asia. After the reportedly destructive Kalinga War, Ashoka converted to Buddhism and shifted from an expansionist policy to one focused on humanitarian reforms. The Edicts of Ashoka were erected throughout his empire, containing the “Laws of Piety.” These laws prohibited religious discrimination and cruelty against both humans and animals. The slaughter or capture of prisoners of war was also condemned. The Edicts emphasize the importance of government tolerance in public policy.

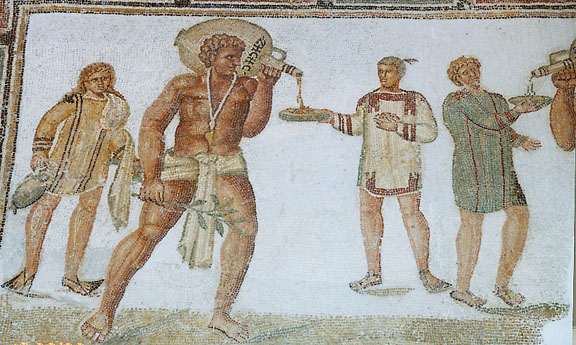

Slavery in Ancient Greece (1,200 to 30 BC) played a vital role in shaping the social and economic structure of the society. Unlike modern concepts of slavery based on race, ancient Greek slavery was an accepted part of Greek life, embraced by both elite and common people. Slaves originated from diverse backgrounds, including war captives, piracy victims and individuals sold into slavery due to debts or poverty, comprising about 30 to 40 percent of the urban Greek population.

In Rome from 753 BC to 565, a Roman “citizen” was entitled to an "ius gentium” or “jus gentium" simply by virtue of his citizenship. The concept of a Roman “ius” is a precursor to the idea of a right as understood in the Western European tradition. The word "justice" is derived from “ius.” Human rights legislation in the Roman Empire included the introduction of the presumption of innocence by Emperor Antoninus Pius and the Edict of Milan by Emperor Constantine the Great, who established freedom of religion. One of the earliest uses of the phrase “human rights” we have is frowa Roman Christian Tertullian, who discussed religious freedom in the empire. He described "fundamental human rights" as a "privilege of nature.”

Roman greatness was built on the backs of its slaves, often prisoners of war. Unskilled or low-skilled slaves worked in fields, mines, and mills with few chances for advancement and little hope of freedom. The possibility of manumission and subsequent citizenship was a key feature of Rome's slavery system, leading to a significant number of freedpersons in Roman society. Skilled and educated slaves—such as artisans, chefs, domestic staff, personal attendants, entertainers, accountants, educators, civil servants, and physicians—held a more privileged position and could hope to gain freedom through several legally protected paths.

The concept of human rights during the medieval ages (5-15 AD) originated with the Divine Right of Kings, which was an extension of the political doctrine supporting monarchical absolutism. It claimed that kings derived their authority from God and could not be held accountable by any earthly authority. The divine right theory can be traced back to the medieval idea that God granted temporal power to rulers, paralleling the divine authority given to the church.

Abuses by the Crown of England caused conflict between Pope Innocent III, King John and the English barons over the King's rights. This conflict led to the creation of The Magna Carta, a charter issued in 1215, which required the King to relinquish certain rights, follow specific legal procedures and accept that his authority could be limited by law. It explicitly protected specific rights of the King's subjects, whether free or unfree—most notably the writ of habeas corpus, which allows an appeal against unlawful imprisonment. The Charter established the principle that no one, regardless of station, was above the law.

The doctrine of Divine Right eventually declined as the idea of personal freedom grew, rooted in the concept of natural law. Philosophical thinking during the later part of the period was heavily influenced by the writings of Christian thinkers like St. Paul, St. Hilary of Poitiers, St. Ambrose and St. Augustine. Augustine was among the first to analyze the legitimacy of human laws and try to define the boundaries of laws and rights that occur naturally, rooted in wisdom and conscience, rather than being arbitrarily imposed by humans. He also considered whether people were obligated to obey unjust laws.

A few years later, Martin Luther’s Protestantism sparked a religious revolution across Europe. Later, Spain's conquest of the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries triggered heated debates about human rights in colonial Spanish America. This led to the enactment of the Laws of Burgos in 1512. Its provisions included regulations on child labor, women's rights, wages, and suitable housing and rest, among other issues.

Later, when Machiavelli published The Prince in 1532, the Church condemned it and actively fought to suppress it. Machiavelli removed morality from politics, demonstrating how rulers stay in power and how others could possess it. The book was seen as highly subversive by European elites, leading to its suppression for centuries.

Several 17th and 18th-century European philosophers, especially John Locke, expanded the concept of natural rights, which is the belief that people are inherently free and equal. Lockean natural rights did not depend on citizenship or any state laws, nor were they necessarily limited to a specific ethnic, cultural, or religious group. Locke believed that natural rights derived from divinity since humans were created by God and his ideas played a key role in shaping our modern understanding of human rights. However, his writings were so revolutionary that they had to be published anonymously in 1663. Later, in 1689, the English Bill of Rights was enacted, which affirmed fundamental human rights, most notably freedom from cruel and unusual punishment.

The idea of natural rights greatly influenced both the American and French revolutions (1776 and 1789) and the movements they sparked, leading to the creation of the U.S. Bill of Rights and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in France. The Bill of Rights, authored by James Madison, listed specific rights such as freedom of speech and protection against self-incrimination. Likewise, the Declaration outlines a set of individual and collective rights that are considered universal, not only for French citizens but for all people without exception.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, primarily authored by George Mason, outlines several fundamental rights and freedoms. Later, the United States Declaration of Independence, mainly written by Thomas Jefferson, includes principles of natural rights and famously states "that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Philosophers like Thomas Paine, John Stuart Mill, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel explored the theme of universality during the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison wrote in “The Liberator,” an anti-slavery newspaper, that he was trying to enlist his readers in "the great cause of human rights.” Therefore, the term "human rights" likely came into use sometime between Paine's "The Rights of Man" and Garrison's article.

In 1849, Henry David Thoreau wrote about human rights in his treatise ''On the Duty of Civil Disobedience,'' which influenced human rights and civil rights thinkers of the era. In 1867, U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Davis, in his opinion for Ex parte Milligan, stated: "By the protection of the law, human rights are secured; withdraw that protection and they are at the mercy of wicked rulers or the clamor of an excited people.”

The foundation of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the 1864 Lieber Code, and the first Geneva Convention established the basis of international humanitarian law, which was further developed after the two World Wars by the United Nations.

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw major advances in human rights, including the abolition of slavery and the expansion of other political rights, especially universal suffrage. The horrors of the World Wars led the global community to pay greater attention to human rights. In 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), establishing a worldwide standard.

The Declaration encourages member countries to promote various human, civil, economic and social rights, asserting that these rights are part of the "foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world.” For the first time in Western history, it established fundamental human rights to be universally protected. The Declaration includes core principles such as dignity, liberty, equality and brotherhood, along with rights related to individuals; their relationships with others and groups; spiritual, public and political rights; and economic, social and cultural rights. The Declaration serves as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and nations. Unfortunately, its adoption is voluntary.

"Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law."

The origins of United Nations human rights law trace back to the abolitionist movement, which sought to end slavery globally. It also stems from the traditional protection of minorities from religious, racial, and national discrimination within countries through unilateral, bilateral, and multilateral treaties, first established in the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. Labor unions also played a role by creating laws that give workers the right to strike, improve working conditions, and regulate or prohibit child labor.

The inclusion of both civil and political rights alongside economic, social, and cultural rights in the Declaration was based on the belief that all human rights are indivisible and closely connected. Although no member states opposed this principle at the time of adoption — and the declaration was approved unanimously, with the Soviet Bloc, apartheid South Africa, and Saudi Arabia abstaining — this principle has faced significant challenges since its introduction.

Throughout the 20th century, many other groups and movements achieved significant social change in the name of human rights. These are too numerous to list, but they include the women's suffrage movement, which successfully secured voting rights for many women and the American Civil Rights Movement, which fought to protect rights that had been systematically denied throughout the American South.

National liberation movements in the Global South gained independence for many countries from Western colonial rule, with Mahatma Gandhi's leadership of the Indian independence movement being especially influential. During the period, movements by ethnic and religious minorities for racial and religious equality succeeded in many parts of the world.

The UN has adopted several other treaties that build on the UDHR, creating non-binding agreements to prevent specific abuses like torture and to protect groups such as women, children and persons with disabilities. They indicate the future direction of compassion for humankind.

The UN Declaration was followed by the European Convention on Human Rights, a binding treaty drafted by the Council of Europe in 1950 and signed by 47 of 51 participating countries. The Convention includes 18 articles, 13 of which guarantee rights such as:

"The right to life, the prohibition of torture and the prohibition of slavery. The right to liberty and security—except in cases of judicial imprisonment—, the right to a fair trial, freedom from retroactive punishment and the right to privacy."

It prohibits illegal police searches and legally protects private sexual activities, freedom of thought, conscience, religion, assembly, marriage, expression protection from discrimination.

It grants the right to seek remedy – anyone who believes their rights have been violated can submit a petition to the European Court of Human Rights to have their case heard and their grievances addressed and redressed.

Twenty of the 47 signatories adhere to an additional protocol expanding this protection to include discrimination in any legal right. The United Kingdom later enacted the Human Rights Act of 1998, which integrated these rights into UK law and authorized English courts to enforce them. Unfortunately, the adoption of these principles remains optional in many parts of the world.

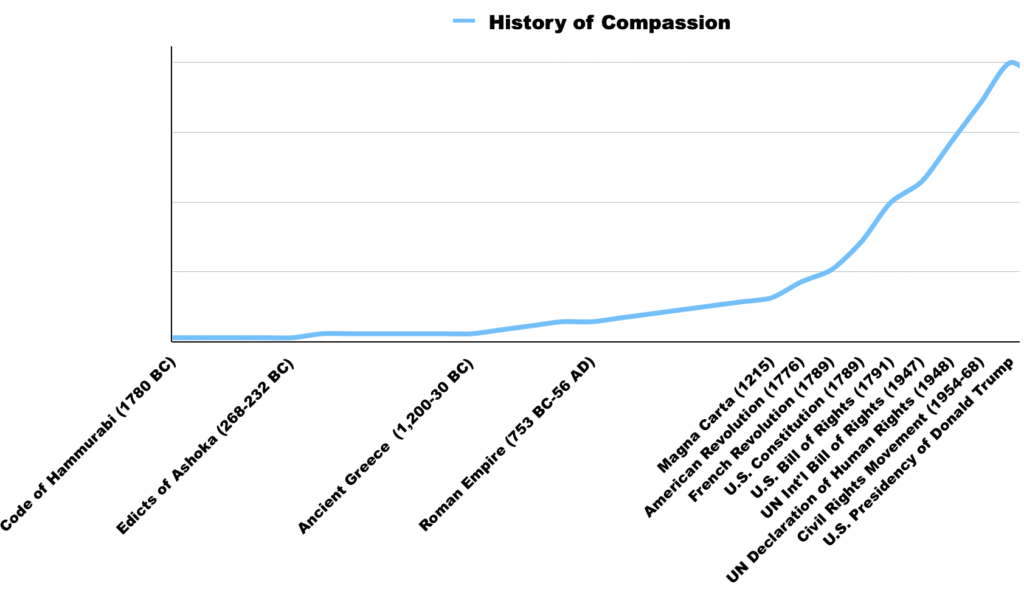

Looking at this list, it’s clear that the journey from the Code of Hammurabi to today has been arduous. So yes, we have made notable progress. If we trace the development of compassion, it would look something like this:

Yet, around the world, some groups are still denied what the rest of us now consider to be basic human rights. And even closer to home, we have made great progress, but still have a ways to go to match the compassion encouraged by the spiritual teachers mentioned earlier. We still face White Supremacists and Nazis, prejudice against minorities, gays and immigrants as well as issues related to female equality. And so long as half of the world’s wealth resides in the top 1% of the population, that is going to be a recipe for trouble

In the future, we will need to provide care for the mentally challenged and offer help, rather than simple incarceration, to those who break the law. And perhaps someday we will extend our compassion to include wild animals and the planet itself.